Some people go on Erasmus to Paris, Heidelberg, or Lisbon during their studies. I almost applied for a semester in Denmark a few years ago, but my first major student exchange was actually… going to the pole. The North Pole.

I mean, the North Pole is a dot in the ocean/on the ice, so not the pole itself, but an archipelago called Svalbard. For many people in Poland, it is better known as Spitsbergen – that is the name of its largest island. But yes, that is where the Stanisław Siedlecki Polish Polar Station in Hornsund is located, that is where polar bears live, and that is where I studied for six weeks. Cool, right? Come on, you’ll find out more.

There is an amazing place in the Arctic archipelago where students and scientists from all over the world come together to teach, learn, and conduct research. In some months, the sun never sets, and in others, it never rises. From the windows of the classrooms, you can see the fjord and steep mountains, and on your way to the store, you can admire at least two glaciers. After class, students drop everything and go to the mountains, and in the evenings they meet in one of the three open bars or at the refrigerator with frozen pizza in the store. On your way to class, you hear sled dogs barking, excited about training. No one locks their doors in the city, and there are more snowmobiles than people on the streets.

Welcome to Svalbard. Welcome to UNIS.

Planning

The beginning

I owe this idea to a close one who, almost three years ago (what a long time ago!), sent me these dream-like scientific courses in Svalbard, saying that we should do them someday and that they are better when you’re a master’s student. I was still doing my bachelor’s degree at the time, so I knew I would have to wait a while. But the idea stuck in our minds. If you want it to stick in yours too, here’s the website: https://www.unis.no/studies/

Months turned into years, years turned into completed studies and defended first theses. In September 2024, I completed my bachelor’s degree in biology and began my master’s studies. I immediately started looking for interesting courses at UNIS, ones that would combine my interests with those of a close one so that we could have this experience together.

After defending my bachelor’s thesis on molecular methods in the study of gray wolf ecology, my heart skipped a beat when I saw the course “Arctic Marine Molecular Ecology,” and I decided to take it. The date? September 2025. Application deadline: March 1. Let’s do this.

We’re applying!

We gathered the necessary documents (mainly proof of completion of previous studies and certificates of further studies) and applied at the end of February. All that was left to do was wait, right?

No. It’s the end of the world, six weeks of classes. Flights, accommodation, food – who’s going to pay for all that? With a clear head, knowing that we didn’t have the results yet, we started asking around and looking for someone who could fund such a trip. We estimated that it would cost PLN 15,000 per person (around 3-4 thousand euro). Unfortunately, at that time, our university did not have any scholarship agreements with Norway, Erasmus was not an option, and the Institute of Geophysics of the Polish Academy of Sciences did not have any open scholarships, which we had seen a year or two earlier. Things were starting to look dicey. If we got in, how would we pay for the trip?

*The exact costs will be in a separate post, and when it appears, I will put a link here. For now, you can find general information further down in the post.

March 27. We receive an email from UNIS saying that one of us has been accepted for the selected course and one is on the waiting list. I was on the waiting list.

I didn’t take it very well, I must admit – after all, it was a big dream, running around dean’s offices and other institutions for weeks, a lot of work and hope. I was really worried that it wouldn’t work out.

April 4. We did it. We both got a spot.

Getting a milion things done before leaving

The most important thing: find funding.

Hope came only at the beginning of May, when I discovered the possibility of applying for a scholarship/travel grant under IDUB. What is it?

“Excellence Initiative – Research University (2020-2026)” is a programme of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, which gives the University of Warsaw opportunities to raise the level of quality in scientific activity and education and, as a result, to increase the international prestige of the University’s activities.

This is how IDUB is explained on its page.

There were some problems with the open call for Student Mobility (which I was interested in, luckily they were accepting applications at the time), but that’s a story for another day. The most important thing is that I submitted my application in June (or was it at the end of May?), and at the end of June I received information that the funds had been granted. They were sufficient to cover most of my costs. My close one had to find other ways to raise funds, but in July it was clear that at least half of our total costs would be covered, we had savings, and we could start considering this trip for real.

In July, we bought plane tickets and applied for a dorm room. The system is synchronized and connected, and every person studying at UNIS has the opportunity to apply for accommodation during the semester through the website of the company that manages the dorms.

We got the student accomodation, and at the end of August, we finalized the insurance, which we arranged on our own, and after buying a million extra woolen layers, mainly on Vinted (lovely app if you don’t kno it!), we were ready for a new chapter in our lives. Cold, unique, and dreamlike. A trip to Svalbard.

Instructions for studying in Svalbard

For those who would like to experience such an adventure on their own:

- Choose a course on the UNIS website, taking into account your education and experience. The website will guide you through the application process. If you are studying in Norway, good for you, you can simply go there on an exchange program and it should be much easier. Consider whether you want to apply for one course or a set of courses.

- Once you’ve been accepted (congratulations!), arrange accommodation through the Samskipnaden website, buy insurance (make sure it covers extreme sports if you plan to go hiking in the mountains and on glaciers, helicopter rescue/transport, and something that translates as movable property insurance) and flights.

- Financing? Talk to your university – UNIS itself does not offer funding. Don’t give up, determination is the first step to success. Seriously, if it weren’t for my persistence, I wouldn’t have gone to the end of the world.

- Equip yourself according to UNIS recommendations: 3xW. Wool. Windproof. Waterproof. Believe me, it will come in handy 😉

- Have fun!

Okay, so how was it??

Unbelievable.

This post is going to be long, but to keep it somewhat manageable, I have to divide my activities in Svalbard into two posts. In this one, I will discuss my scientific activities, what I did during the course, and what it was like to study at UNIS. I will leave my subjective activities and experiences outside the course for the next post (when it’s ready, I’ll add a link here!).

The „Arctic Marine Molecular Ecology” course at UNIS

This course included everything that a small but well-designed scientific project with an educational component should include.

There were lectures, seminars, presentations, and group work. There was fieldwork, hours spent in the lab and in front of laptops, trying to analyze and piece together the data we had collected. There was report writing and an oral exam.

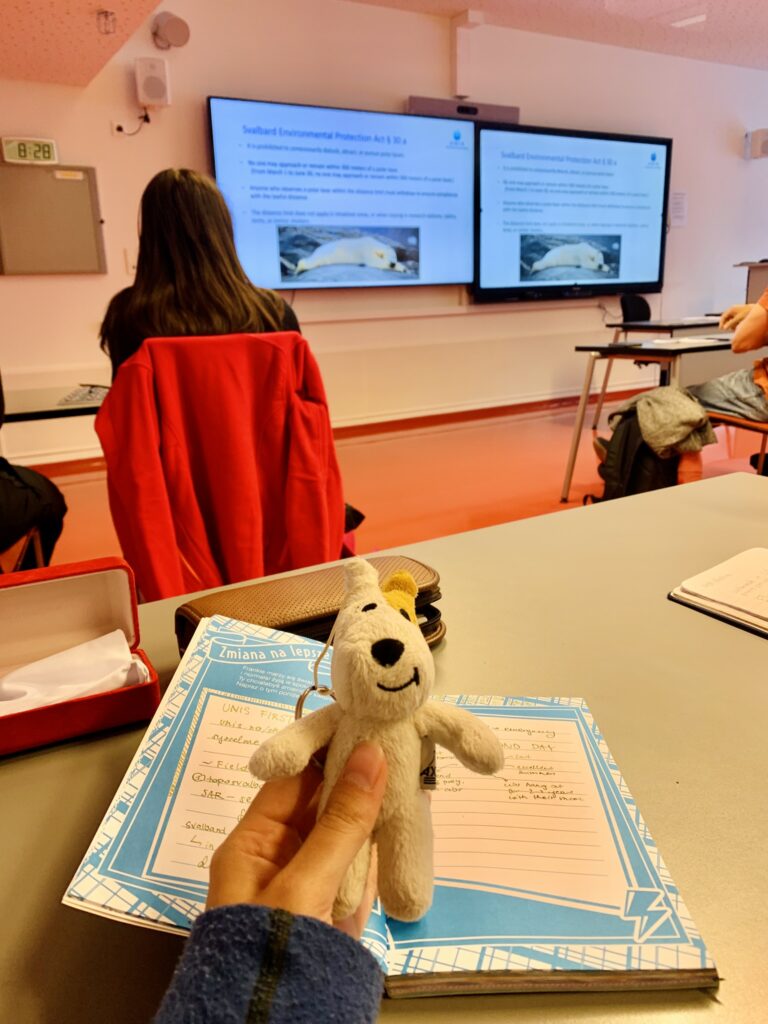

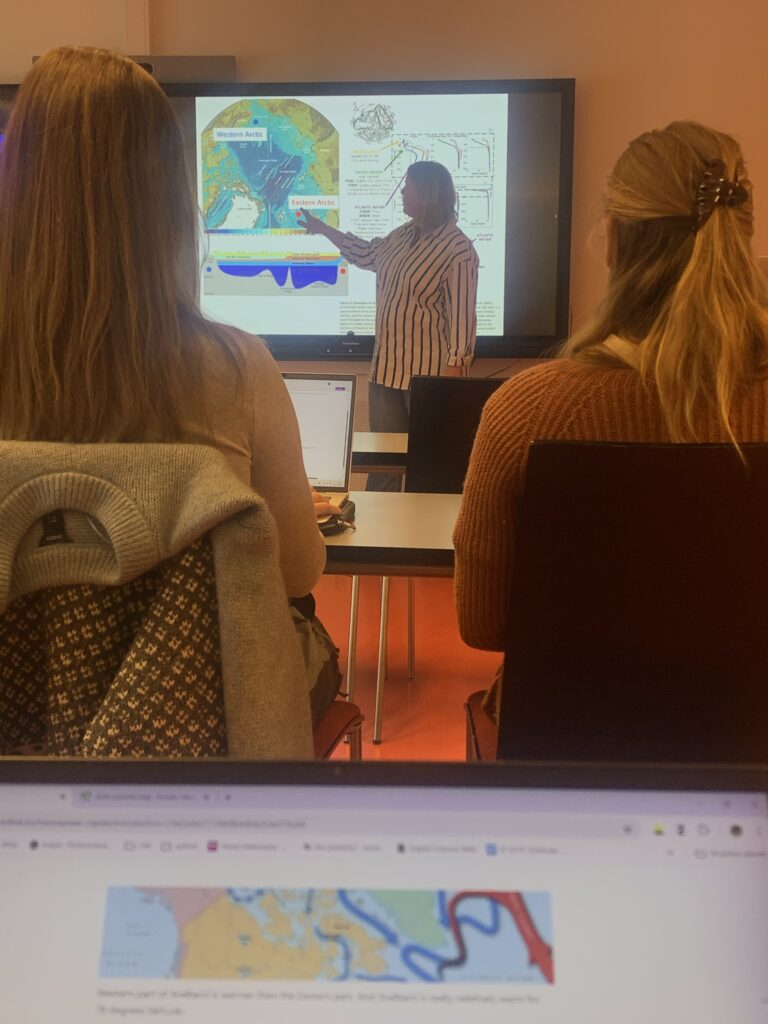

Before I move on to broader conclusions and more detailed descriptions, here are a few photos, arranged chronologically, which show the work quite well.

Part One – organization, training, lectures

From the very beginning, I felt well taken care of. In September, I received information about what I should know before arriving and which topics I should remind myself of. We were given the first schedule for the course with dates, times, and types of activities. The long days in the laboratory stood out, but so did the field work on the ship. After all, it was Arctic MARINE molecular ecology, right? We were also briefly presented with the topics of the group projects – there were four to choose from, and our task before departure was to send the instructor information about our scientific backgound and project selection.

I was one of the lucky ones who got the project of their first choice :))

Think, plan, and think again about what you are doing – safety according to UNIS

The first few days on site were devoted to safety training. This is not occupational health and safety (BHP) at a typical Polish university, where a third of the students sleep, and the rest play games, scroll through their phones, or chit chat. We are in Svalbard – everyone thinks of bears as the main threat, but contrary to appearances, the weather and the human factor are often worse. They teach us to plan, think and understand the Arctic reality.

Safety training is tailored to the course being taken – it is modular, and you complete the parts that are relevant to you. This means that almost everyone who is taking courses in the coming weeks (it’s September, remember) has taken part in shooting training, polar bear safety, and boat safety.

So I was trained in shotgun shooting, taught about the basic biology and behavior of polar bears, tested on setting up tents in demanding conditions, and told to swim in the fjord in survival suits.

In the photo, you can see me somewhere on the right – don’t be fooled by those survival suits, it was cold anyway. I mean, under the wetsuit I was wearing woolen leggings, trekking pants, a woolen base layer, a woolen sweater, and two pairs of socks. But my hands were freezing in those neoprene gloves. You see, without those suits, there is no chance of survival in the water: hypothermia sets in quickly and effectively. That’s why we were taught to move around in them, swim, and most importantly, wait for rescue by helicopter.

After completing the three-day training (in my case), we received a certificate that allowed us to participate in field work. That’s why attendance was mandatory.

Everyone working or studying at UNIS must undergo this training. There is a refresher course every six months. The training courses vary slightly depending on the season – when I left, I saw that the next course already had avalanche response classes in the syllabus. In our case, this was not considered necessary. After all, there wasn’t that much snow – the first major avalanche was reported in the last few days, after we had already left. Good timing 😉

I must admit that I have never before been presented with safety training in such a factual and interesting way. I was delighted by their Buddy Program, which involves pairing up with “buddies” who look out for each other. In the field, no one wants to be the slowest or report that they have blisters and need a band-aid, or say that they are starting to feel weak. That’s what your buddy is for – tell them, and they will tell the rest. Buddies are supposed to look after each other, keep an eye on each other, and take care of each other. If one buddy does something risky, the other will notice and react. And the pressure is off you, because you’re not on your own. We all understand that it’s better to slow down than to deal with fainting person in half an hour in a place with no cell coverage and no shelter. So we take care of each other!

Buddies also keep an eye on each other when it comes to weapons – one watches everything the other does, and what’s more, the first cannot proceed (e.g., load or unload a weapon) without a verbal confirmation from the second. Safety first.

Doesn’t that sound beautiful? It does. And what’s even more beautiful is that I was able to be part of this community for over a month.

We also had an interesting training session on group dynamics, but if I were to tell you about everything, the internet wouldn’t be enough for such a long post. Maybe another time.

Lectures and seminars

I still don’t understand why some Polish lecturers don’t share their lecture slides. What are we supposed to do with them? Send them to younger students? Someone from another university? Or, God forbid, study properly for the exam?? That would be a catastrophe, right??

There was no such problem here – the literature was available from the beginning of the course, and the slides were posted before or immediately after the lecture. Attendance was properly checked perhaps twice, at the beginning of the course, or when necessary. There were fourteen of us, including me – the main lecturers quickly learned our names and who else we might be waiting for.

No one made a big deal about being late for lectures, for which I will be eternally grateful to every lecturer, because, as we all know, the connections in my head weren’t done properly, and I have many virtues, but being on time is not one of them. Phew, I said it.

The difficulty and complexity of the lectures grew exponentially. From the first ones, when I wondered if maybe I knew too much, to the last ones, where during the lunch break I needed to look at the snow outside the window to get my brain back to the desired consistency from its liquid state. The lectures were given by people who were experts on the subject – some flew in for a few days from Tromso or Oslo, but there was also someone from Barcelona!

We had seminars devoted to discussing scientific papers, which were well organized and conducted. There were computer labs with genetic programs and R (a programming language beloved by biologists and some statisticians), during which everyone’s brains were steaming and coffee breaks were necessary.

All in all, a course well prepared, interesting stuff learned.

Part two – group projects

After this trip, I became an unquestionable fan of project-based learning. It’s not that everyone does the same exercise to learn the method and assimilate the material, but rather that we divide the group into teams, each team gets its own project and works on it. The feeling that it’s “your” data, materials, and results really motivates you to work. And how do you then share the knowledge between the groups? Presentations, reports, and saying that knowing of all groups’ reports is required for the exam. Nothing motivates you more to sit together and tell each other what you did, how you did it, what worked, and what didn’t ;))

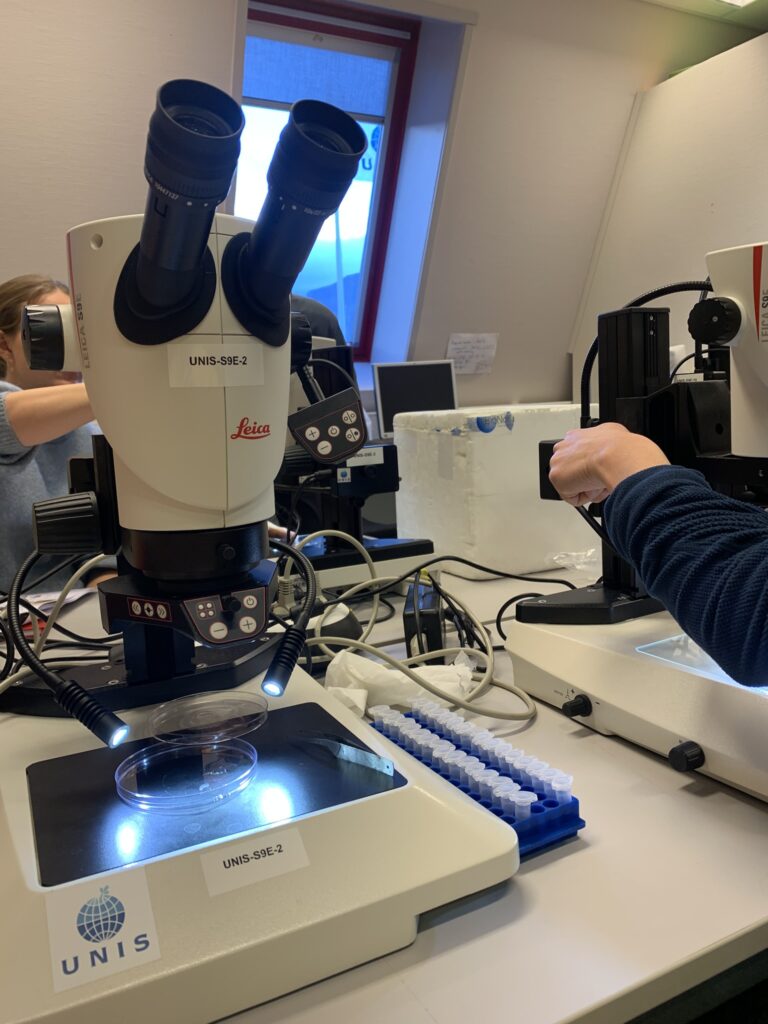

For six weeks, together with my team (there were four of us), I worked on the ecology of a small copepod with the charming name Pseudocalanus. We had information about what needed to be done with it, what was possible, and the rest was up to us. We figured out what interested us most about it and based our sampling in the field, laboratory work, and further analysis on that.

The fieldwork was real fieldwork, in the flesh. We spent 24 hours on the ship, slept on it, ate with the crew, and took turns working either on deck or in a container that served as our mobile lab. It was an amazing experience, and I am very grateful that I had this opportunity.

The lab work was well coordinated – each team had a supervisor who provided advice and assistance. We shared the lab space with all the other groups, so we had to reserve the electrophoresis apparatus on the very first day ;)) There was no tension between us, we tried not to disturb each other, and since the topics were quite different, the equipment we used also differed.

The lab work was well thought out – we were informed for how many days the labs were reserved for us, and we agreed on specific times when we would work with each other and our supervisors. This allowed us to be in the lab when it made sense and take flexible breaks (preparing PCR takes a while, and once the reaction is happeing on itself, you can enjoy your lunch).

No one told us exactly what to do. Help was always available, and I went once with the result of one analysis and asked, “What am I supposed to do with this?” because the result was far from what I expected. But we also sat together with the team for three hours in the cafeteria trying to figure out the problem we encountered – ultimately with success. We were treated like adults who are able to organize and plan their work themselves. Cool, right?

For the purposes of group work, there were days when rooms were rented for us and we were told that we could use them. Sometimes we worked during the designated time, and sometimes we took advantage of the weather and met in the evening to make up for the time spent hiking in the mountains. Let me tell you right away that there is nothing more arctic than going to the mountains when the weather is ice and catching up on work afterwards. I recommend this approach in life in general. Very little really needs to be done here and now and at this moment.

We had assigned days off from classes to write the report, which later accounted for 40% of our individual grades. Project presentations were required, but were not graded, served as a test whether what we had was meaningful and worth including in the report. This made the final touches on the report much easier.

The report was due on Monday, and the oral exams were held on Thursday and Friday – we also had no classes during those few days and complete freedom to prepare well for the exam. In my opinion, there was enough time to revise.

I am still waiting for my grade, but I am optimistic – I will gain much more from this course than just 10 ECTS points and a grade. A practical understanding of the techniques used, the ability to design an entire study, from sampling to the selection of statistical analyses. There were questions like that on the exam, so I’m pretty sure about that ;)) And above all, the people – it’s an honor to study with people who are so eager to get things done. From different parts of Europe, with different scientific experiences and life paths that led them to the pole. Well, I miss them and I will miss them!

Part Three – UNIS and its studying culture

Oh, my! There is no end to the wonders, so get ready!

I have already mentioned the available slides, not killing people for being late when it is not crucial (I was not late for field classes and safety training!), and being kind. This is just the beginning!

UNIS, as a building, has many rooms, a large cafeteria, a library, laboratories, storage facilities where security people reign supreme, and a million other elements. In the first week of classes, each student received a card that could open the entrance door to UNIS at any time. 24/7. I happened to be there late – 9 p.m., 10 p.m., no problem. Can you trust your students? Yes, you can.

Of course, the card would not open everything – offices, parts of labs, or staff areas. But the classrooms were always open, so as long as they were not reserved, we could use them. Once, when I left my pencil case and notes in one of them, their availability came in very handy – after 9 p.m., I took a walk to UNIS and picked up my things from the classroom where I had left them.

Next: UNIS has a huge cafeteria, which is the largest room in the entire building, not counting the hangar/warehouse. I don’t even know how many people it can fit – 100? Probably more when seated, and definitely all UNIS students when standing. During the day, there is always someone there, whether it’s someone popping in for coffee, sitting down with a laptop, or eating lunch. Every Friday, the cafeteria turns into a meeting and party place (so called Friday gatherings!) where staff and students can get together, have fun, play beer pong, or chat. I will remember the Halloween party for a long time :)) Is it possible to open the cafeteria for more then only 5-7 hours a day? Yes, it is. Is it possible to allocate a large space for it, because everyone knows that the most important thing is conversation and the exchange of ideas at the university? Yes, it is. Polish universities should watch and learn.

Of course, you can eat in the cafeteria. From what I remember, meals are served from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., with plenty of options to choose from. Due to the price (soup costs PLN 15-20, so 5-6 euro, main courses are sold by weight, I ate for PLN 35, around 12 euro), I usually brought my own lunch and reheated it in the microwave available in the cafeteria. Oh, and there is a huge wood-burning fireplace in the middle, so in the evenings you can light a fire and sit in armchairs around it. Did I mention that?

Another element: breaks. This should be the norm, but it is not yet in my country (hi there Poland). Classes do not continuosly last longer than an hour, unless otherwise agreed with the students (sometimes I stayed in the lab a little longer to finish something). Even those 10-15 minutes are enough to stretch your legs and drink some coffee. But that’s nothing – the best part is the lunch break. It usually lasts an hour, but for us it was regularly 1.5 hours. It happened once or twice that it was shorter. Everyone takes this break seriously because you need to eat, rest, and talk. The cafeteria is then bustling and filled with people. This usually happens between 11:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. Such regular meal times are really important – your body immediately feels better ;))

Everyone is on first-name terms – the instructors don’t ask to be addressed as professors, because no one needs to create distance in this way. And so we treat each other with respect – us towards the instructors, and the instructors towards us. If we agree on something, both sides stick to it. It feels silly to even write about it, because it should be obvious – we treat each other like human beings. It’s that simple.

The way people dress and carry themselves is quite interesting – in Svalbard, partly out of tradition and partly out of practicality, it is required to take off your shoes in many places. It is no different at UNIS, so you either walk around in socks, sneakers (which you leave at the entrance), or slippers. This adds to the homely atmosphere. As for how people dress, the vast majority wear outdoor clothing, because here, the 3-minute walk from the dormitory to the university in harsh weather conditions is a challenge without outdoor clothing*. Of course, some people brought jeans from home and sometimes wear them, but trekking pants and warm sweaters or fleeces dominate. The practical aspect is the most important – warm and comfortable, just like at home. And for us students, UNIS becomes sort of a home.

*I have to admit that I wore warm shoes instead of hiking boots to the exam, which resulted in me crawling on all fours for part of the way. I’m not kidding. I took a shortcut instead of following the main road, and everything was so frozen that my attempts to walk ended with my face on the ice. I politely discarded what remained of my dignity and crawled a few meters on all fours. I have no regrets – watching people slip and slide from the windows of the cafeteria is a daily activity during lunch, and maybe someone smiled when they saw me struggling with the ice ;))

A dormitory that guarantees each person/couple a separate bathroom. One fully equipped kitchen for 5-10 people. It has a TV, sofas, a large table for eating together, and lots of necessary equipment. Including toasters and sometimes even simple coffee makers! Not to mention a microwave and oven. Is it possible? Yes, it is. This creates unique kitchen communities – no one is alone. Unless you rent a room with your own kitchen, which some people do (including me and my close one), then you don’t share the kitchen with anyone else. But it’s a great idea, I’ve been in many kitchens, whether for get-togethers, games, or watching something. And borrowing flour or baking scales from each other was an everyday occurrence.

After leaving the dorm, I was greeted by such sights:

I think that’s enough for my first Svalbard blog post. There will be more, I promise! If you have any questions or comments, please get in touch – the “contact” tab will direct you to me. My adventure in Svalbard will stay with me for the rest of my life, and I can’t wait to tell you more about it. Because there’s still hiking on a glacier, sauna and jumping into the sea, dance classes, local art exhibitions, concerts, a weekend in a cabin without water, electricity, or a toilet, and much, much more. I want to share what I took to Svalbard, what I didn’t take, and what I recommend having. And I want to share a general cost estimate/budget! Because it’s important to many people – it was also for me.

Don’t be afraid to dream, and then make those dreams come true. It’s worth it.

That’s all from me for today. Take care :))

Musisz być zalogowany, aby dodać komentarz.